The Watchmen Doomsday Clock vs. Ours

Who Watches the Watch, Man?

You guys ever seen Watchmen? I have. A lot. For the uninitiated, it’s a dystopian superhero film based on a graphic novel by Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons and John Higgins. The film takes place in an alternate history: it’s 1985 and the Cold War has reached boiling point, with the US and the Soviet Union on the brink of total nuclear armageddon. Nixon has remained in power for 16 years, leading America to victory in the Vietnam War with the aid of one Dr. Manhattan, a glowing blue man with God-like powers as the result of being caught in an intrinsic field generator. He’s just one of the many Watchmen, a motley crew of rejects, alcoholics and tragically vain humans dedicated to saving America. Even if it kills them. All of them.

Needless to say, the political satire is rife, if unsubtle. When I watched it for the first time almost ten years ago, there was one symbol in particular that stood out to me: the Doomsday Clock. This figurative timepiece, used to represent humanity’s impending destruction, was such an interesting concept to me, and one that seemed natural arising in such a dystopian, comic book setting. Of course people would use a literal countdown to thermonuclear war in this reality. What more would could there possibly be to talk or think about, with a criminal in office, foreign relations disintegrating and threats of nuclear missile attacks looming?

You see where I’m going with this, right? Turns out – and I sincerely didn’t know this until I saw the film for, like, the fifth time – the Doomsday Clock is real. Life imitates art imitates life, apparently, because the actual Doomsday Clock was conceived of in 1947 in the wake of the international reckoning of WWII. Since that time, the maintainers of the clock begin every year by assessing the potential for a man-made global catastrophe based on a number of factors, e.g. international diplomacy, climate change, ostensible technological advances etc. And each year, they move the minute hand either closer to or further away from midnight, analogising our statistical likelihood of annihilation.

Now, people can argue over the veracity and scientific merits of such a clock. Some might consider it simply a cosmetic appropriation of human will and behaviour which, on global scale, is virtually impossible to predict. Or worse, the clock can seem like an attempt to objectively determine danger through an inherently subjective (i.e. political) lens. Regardless, the Doomsday Clock remains an intriguing symbol of our current trajectory as a planet and collective society. For over 70 years, it has stood for a wide-reaching and multi-faceted assessment of our ability to get along. At the very least, its existence can serve to colour our understanding of the world’s current predicament and it’s likely chance of survival going forward.

So, back to Watchmen: it is a deeply pessimistic film. It’s also very kitsch, kinda goofy and (except for Suicide Squad) possessive of one of the most overreaching soundtracks in modern cinema. But the dark thread that ties it all together – and makes it so rewatchable – is its utterly unimpressed view of humanity. The film doesn’t end with total nuclear destruction, but it does feature a lot of senseless death, unwilling martyrdom and a degree of moral flexibility and compromise that is frankly unsettling. Once again, this is a world standing on the brink, and the Doomsday Clock setting accurately reflects that: two minutes to midnight.

Guess what? The real Doomsday Clock is currently sitting at two minutes to midnight. I am not kidding. The only other time it’s ever been that close was in 1953, right after the US and the Soviet Union each performed their own thermonuclear weapons tests. Since then, the minute hand has moved all over the place, even getting as far away as 17 minutes from midnight in 1991 after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. But over the last eight years, the trend has been towards conflict, strife and political division. Hence, our current setting: from six minutes to midnight in 2010 to only two minutes to midnight in 2018.

Ok, so what does that mean? Again, how much stock do you invest in a clock that tells you we’re all probably gonna blow up? I thought it was a great gimmick for a superhero movie in my youth; however, after realising its real world existence, I was forced to reckon with the degree to which a gimmick can illuminate hard truths. No, we don’t have flawed, costumed strongmen in the streets blurring the lines between protector and aggressor. Instead, they’re in office.

It’s not just me drawing this parallel. Here are the official explanations for the last two years of the steadying ticking towards midnight:

2017, 2½ minutes to midnight: Rise of neo-nationalism, United States President Donald Trump’s comments over nuclear weapons, the threat of a renewed arms race between the U.S. and Russia, and the expressed disbelief in the scientific consensus over climate change by the Trump Administration.

2018, 2 minutes to midnight: The failure of world leaders to deal with looming threats of nuclear war and climate change.

Finally, let’s return once more to Watchmen. The movie has as happy an ending as is possible under the circumstances: Dr. Manhattan is deceived into allowing his powers to cause wide-scale destruction indiscriminately across the world. In the aftermath, the US and the Soviet Union set aside their differences to combat their new common enemy. Millions die and Dr. Manhattan leaves Earth, which keeps on turnin’. Roll credits.

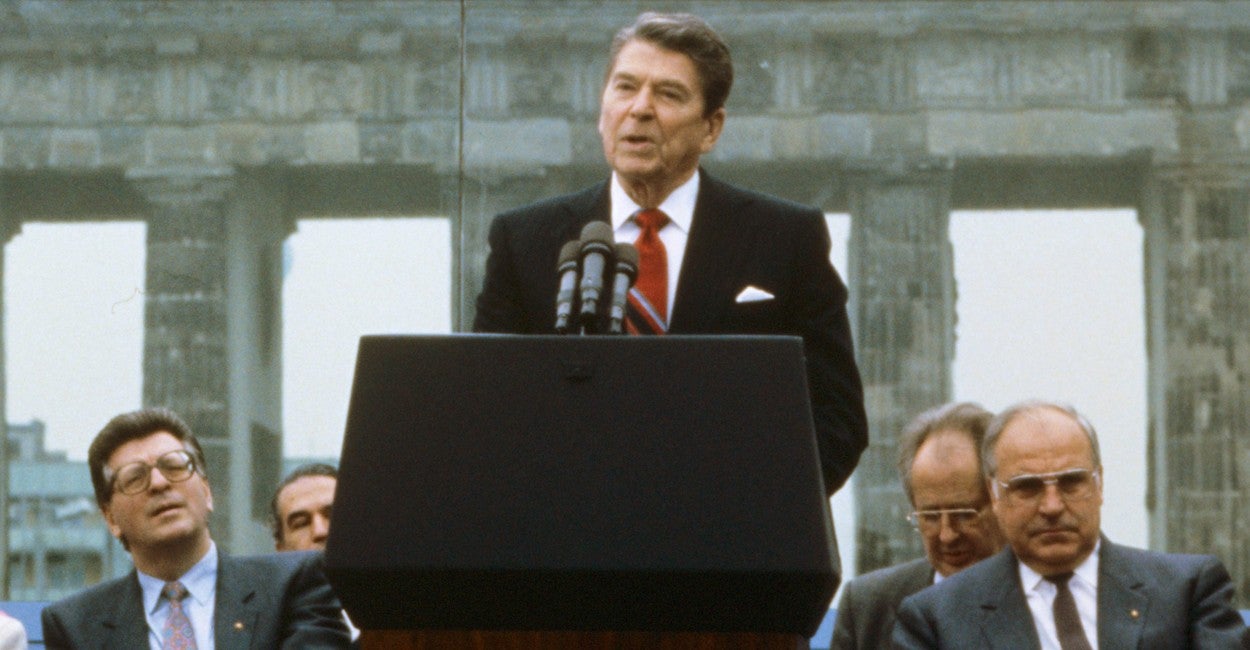

Can we learn anything from this, assuming there is anything to be learned from a comic book adaptation directed by Zack Snyder? I sincerely don’t know. I recently read that President Ronald Reagan, after having watched the apocalyptic drama The Day After in 1983 (arguably the height on the Cold War) was seriously distressed by the film. A diary entry from the former president confirms it left him “greatly depressed”. Four short years later, in West Berlin, the man who staunchly advocated for nuclear armament against the Soviets offered this historic imploration: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

Reagan’s legacy is debatable, but it’s difficult to deny that his actions were a precursor to the relatively peaceful armistice that America and Russia enjoyed throughout the ’90s. Indeed, he was able to act on the same impulse of mutual beneficence that appears in Watchmen without even needing a literal common enemy. Regan’s conception of that threat, luckily, was much more philosophical: the common enemy was annihilation.

Was it all because of a movie? Highly doubtful. Was it somewhat because of a movie? Probable. This is no panacea, of course: even if someone did manage to convince Trump to sit still for the two-and-a-half hour runtime of Watchmen, I’m not sure he has the cognitive acrobatics to conceive of an alternative history. He might even mistake it for a documentary. But the point remains that an artistic rendering of our race’s tendency towards self-sabotage can leave an impact. This can be in any form, and can be taken as seriously or as flippantly as the individual chooses. In fiction, we have Watchmen. In life, we have the Doomsday Clock. And the lines aren’t getting any less blurry.