directed by F. W. Murnau

2. The Last Laugh (1924),

directed by F. W. Murnau

One of the Most Revered Films of the Silent Era Remains Impressive in its Minimalist Storytelling

Every movie you watch requires some suspension of disbelief. To really work, a film needs an audience to be complicit with its fabrications, to agree that just because what you’re being shown isn’t really happening, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t matter. Movies like The Last Laugh (or in the original German Der letzte Mann, meaning “The Last Man”), when viewed in the year 2017, require more than that to be fully enjoyed. For the sake of this movie, you must actively amend everything you know about modern cinema. Basically, you have to imagine this is the first film you’ve ever seen.

Here’s why: presented in a modern context, this movie kinda blows. Beyond the obvious hang-ups most people would have with this sort of film (it’s black and white and silent), its pace and basic-arse story leave something to be desired. In short, a seasoned hotel doorman (legendary silent film star Emil Jannings) is demoted to a more lowly position and it’s pretty embarrassing for him. That’s it. And this thing goes for 80 minutes.

But dismissing The Last Laugh for being beholden to the era it was made in is less rewarding than accepting how much it contributed to the modern landscape of cinema that we now revel in. Virtually every technique directors employ in films these days stems, in some way, from this film and the innovation of its director, F. W. Murnau. Needless to say, in 1924 these were the very aspects of The Last Laugh that made it revolutionary, to audiences and critics alike.

Consider the opening shot of the film, in which the camera – gazing downwards at a busy hotel lobby – slowly descends in an elevator, before smoothly gliding out towards Jannings’ character at the revolving doors. At the time, capturing a shot in motion like this – using a technique referred to as “entfesselte Kamera“, or “unchained camera” – was virtually unheard of. It literally changed the face of cinema overnight, but what’s more interesting is the story behind it: in order to achieve this shot, Murnau had his cinematographer Karl Freund fitted with a camera, which was strapped to his chest. Freund then rode a bicycle into the elevator and out into the lobby, resulting in the fluid take seen in the film.

Similar methods were used for a scene in which the camera appeared to make a miraculous ascent up from the street; in reality, the camera was attached to a wire and sent down below, and the shot was then reversed in editing. And then there’s the scene where the doorman, while pissed as twelve men, sits and feels himself spinning; indeed, as the camera maintains its hold on him in the foreground, the background whizzes by drunkenly. For this effect, Freund placed himself with the camera on a swing which rocked gently back and forth, giving the same floating impression as the previous shots, but to a different end.

There’s something enriching about this kind of trivia, knowing the physical demands that went into making the film appear the way it does. Well-made though they may be, contemporary movies rarely have that laborious essence that informs The Last Laugh. Apart from the ability to reverse shots in editing and superimpose overlapping images (which is done to enhance our understanding of the doorman’s drunkenness later on), nothing here was achieved with special effects. It was conceived before the means to actually film it were available and so, naturally, Murnau simply created those very means himself.

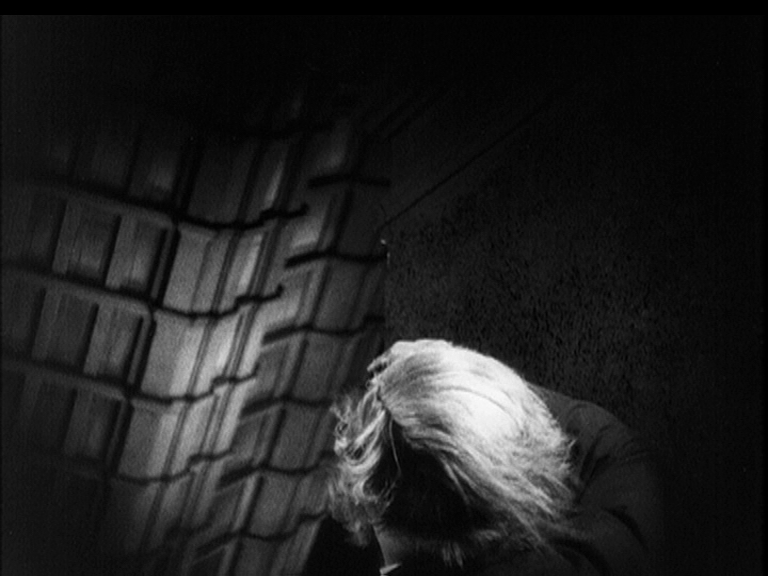

Being a German director working at the height of German Expressionism, it goes without saying that Murnau’s work here has some of the same hyper-stylised appearance that defines that movement. In moments of triumph, the doorman is awash in brightness, but after he loses the job, his uniform (symbolic of his standing in the world) and is forced to work in the hotel washroom, he is cast in shadows. Not the shadows of regular films that suggest depression, but the stark, fractured darkness of Expressionism, conveying a waking nightmare.

Elsewhere, when he passes out from too much drinking, the doorman dreams of himself as the strongest and most able of all workers. Six men – all dressed in smooth black uniforms, their heads and faces a pallid white – attempt to lift a comically large piece of luggage, but are unable. Enter the doorman, gesturing for them to step back, as he lifts the case with one arm and then effortlessly tosses it into the air. The frames of the picture seem to wobble as the camera, bobbing and weaving with an intoxicated jitter, scans the crowd that has gathered, who look on in awe at the doorman’s prowess.

Still, setting aside all the technical innovations and stylistic flourishes of the film, Murnau’s foremost accomplishment with The Last Laugh was in establishing the medium of film as entirely separate from other artforms. His intention was to show how uniquely suited movies are to telling this kind of story and how fully an audience can be manipulated into understanding and experiencing another person’s perspective. He wanted to craft, in the words of the late film critic Roger Ebert, “a machine that generates empathy”.

In order to achieve this, Murnau wished to eschew anything “that is trivial and acquired from other sources”, which is exactly what he did. You see, The Last Laugh contains almost no intertitles as stand in for dialogue or to instruct the viewer as to what is happening, which was incredibly unusual for a silent film. But because of Murnau’s attention to detail (and Jannings’ emotive showing as the doorman), even a child could follow the story as it unfolds.

It’s all there in the doorman’s initial hubris, his chest puffed out and beaming at his position in life, followed by his dejectedness after being sacked. He becomes hobbled and bent over, seeming to recede into himself, as the camera similarly ambles along next to him, reflecting his misery in the wake of his fall from grace. Additionally, many of Murnau’s close-ups and point of view shots allow us insight into the doorman’s emotional frame of mind, and his use of symbolism – as when the doorman turns to see the building he has emerged from crashing to the ground – suggests the figurative notions he has of the world.

All of which is to say there’s basically an extracurricular element to this movie, which will definitely be enough to ward most people off. But knowing the effort that went into The Last Laugh, understanding the impact it had and being able to trace it through the lineage of cinema up to the present day is one of the reasons it remains such an important film. If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to be a time traveller, this is your shot: watch this film with an open mind, forget everything of the world as you now know it and allow yourself to be enveloped by the wonders of a different age.